What makes the Bison Range, and its relation to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, so unique?

The Bison Range, formerly known as the National Bison Range, is an unusual property with distinctive qualities and characteristics, including its past and ongoing ties with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT, or Tribes). No other federal property is similarly-situated to the Bison Range.

Our History

Restoring the land to federal ownership in trust for the Tribes, for continued bison conservation purposes, makes sense in this situation due to the highly-unique circumstances involved, including the following:

The Bison Range is in the center of the 1,250,000-acre Flathead Indian Reservation and consists of 18,766 acres. Over half of the Bison Range borders Indian trust land and waterways. The Bison Range is currently managed as a Wildlife Refuge by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

The Bison Range is in the center of the 1,250,000-acre Flathead Indian Reservation and consists of 18,766 acres. Over half of the Bison Range borders Indian trust land and waterways. The Bison Range is currently managed as a Wildlife Refuge by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

In the 1870’s, CSKT Tribal members sought, and eventually received, consent from Tribal leaders to bring several of the country’s last remaining wild bison over the Continental Divide to start a bison herd on the Flathead Indian Reservation. This was essentially for the purpose of maintaining a conservation herd in response to what appeared to be the plains bison’s imminent extinction. These bison grew into a small herd, which was later acquired by Tribal members Michel Pablo and Charles Allard, who increased it to a much larger bison herd commonly referred to as the “Pablo-Allard herd”. The Pablo-Allard herd ranged freely on the Reservation for decades before having to be sold to off-Reservation interests in the early 1900’s due to the opening of the Reservation, over strong objection from the Tribes, for non-Indian settlement.

In the 1870’s, CSKT Tribal members sought, and eventually received, consent from Tribal leaders to bring several of the country’s last remaining wild bison over the Continental Divide to start a bison herd on the Flathead Indian Reservation. This was essentially for the purpose of maintaining a conservation herd in response to what appeared to be the plains bison’s imminent extinction. These bison grew into a small herd, which was later acquired by Tribal members Michel Pablo and Charles Allard, who increased it to a much larger bison herd commonly referred to as the “Pablo-Allard herd”. The Pablo-Allard herd ranged freely on the Reservation for decades before having to be sold to off-Reservation interests in the early 1900’s due to the opening of the Reservation, over strong objection from the Tribes, for non-Indian settlement.

In the early 1900’s, 18 bison from the Pablo-Allard herd were brought to Yellowstone National Park to augment its dwindling bison herd, which had consisted of an estimated 22 animals by 1902.

In the early 1900’s, 18 bison from the Pablo-Allard herd were brought to Yellowstone National Park to augment its dwindling bison herd, which had consisted of an estimated 22 animals by 1902.

In the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, the United States promised that the Flathead Reservation would forever be the Tribes’ permanent homeland. In exchange, the Tribes agreed to relinquish millions of acres of their aboriginal territory. The Tribes lived up to their promise. Sadly, the United States did not. In 1908-1909, over the strong objection of the Tribes, the United States unlawfully took the land from the Tribes for what is now the Bison Range. The United States had paid about $1.56 per acre for it, which the U.S. Court of Claims held, in 1971, did not constitute fair market value at the time the land was taken. The court therefore held it to be an unconstitutional taking under the Fifth Amendment and awarded CSKT around $231,548 in compensation for what the government should have paid the Tribes when it took the Bison Range land (approximately $14 per acre, based upon the 1912 fair market value rate). Tribal members have for generations believed that no amount of money could compensate them for removal of the Bison Range from their permanent homeland.

In the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, the United States promised that the Flathead Reservation would forever be the Tribes’ permanent homeland. In exchange, the Tribes agreed to relinquish millions of acres of their aboriginal territory. The Tribes lived up to their promise. Sadly, the United States did not. In 1908-1909, over the strong objection of the Tribes, the United States unlawfully took the land from the Tribes for what is now the Bison Range. The United States had paid about $1.56 per acre for it, which the U.S. Court of Claims held, in 1971, did not constitute fair market value at the time the land was taken. The court therefore held it to be an unconstitutional taking under the Fifth Amendment and awarded CSKT around $231,548 in compensation for what the government should have paid the Tribes when it took the Bison Range land (approximately $14 per acre, based upon the 1912 fair market value rate). Tribal members have for generations believed that no amount of money could compensate them for removal of the Bison Range from their permanent homeland.

After the Bison Range was established in 1908, the federal government needed to obtain animals for its initial bison population. An enduring irony is that most of the bison acquired for the Bison Range’s initial herd consisted of the recently-ejected bison from the Pablo-Allard herd, or their descendants, that were bought back from their recent off-Reservation purchasers. The Tribes’ special relationship and history with these particular bison are the sources of continued pride and an ongoing sense of responsibility for their well-being.

After the Bison Range was established in 1908, the federal government needed to obtain animals for its initial bison population. An enduring irony is that most of the bison acquired for the Bison Range’s initial herd consisted of the recently-ejected bison from the Pablo-Allard herd, or their descendants, that were bought back from their recent off-Reservation purchasers. The Tribes’ special relationship and history with these particular bison are the sources of continued pride and an ongoing sense of responsibility for their well-being.

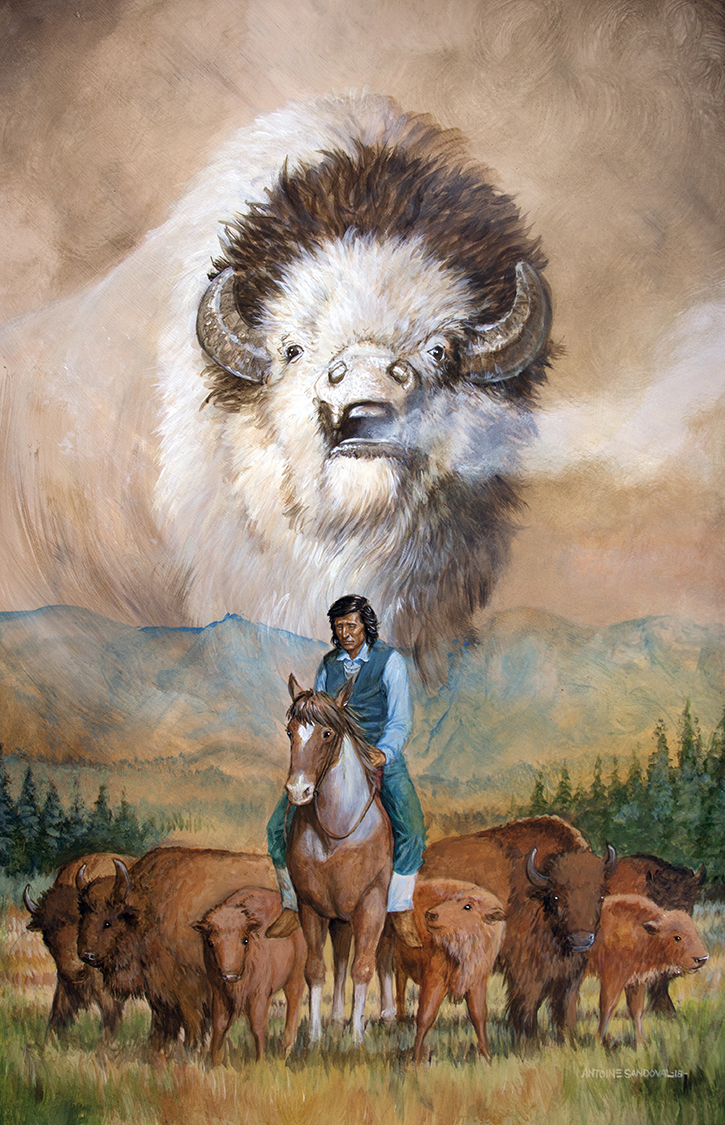

From 1933 through 1959, Tribal members paid many visits to a white bison born at the Bison Range. He was called Big Medicine in recognition of the esteem in which he was held. Big Medicine, a descendant of the Pablo-Allard herd, was a touchstone for Tribal members’ ongoing relationship with the bison at the Bison Range.

From 1933 through 1959, Tribal members paid many visits to a white bison born at the Bison Range. He was called Big Medicine in recognition of the esteem in which he was held. Big Medicine, a descendant of the Pablo-Allard herd, was a touchstone for Tribal members’ ongoing relationship with the bison at the Bison Range.

From 1994 through 2016, CSKT engaged in extensive and repeated efforts towards entering into partnership agreements with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for management participation at the Bison Range. These contracts are authorized by the Tribal Self-Governance Act and two such agreements were in effect from 2005-2006 and 2008-2010.

From 1994 through 2016, CSKT engaged in extensive and repeated efforts towards entering into partnership agreements with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service for management participation at the Bison Range. These contracts are authorized by the Tribal Self-Governance Act and two such agreements were in effect from 2005-2006 and 2008-2010.

CSKT’s Bison Range Self-Governance agreements are exceptional in the country. No other tribe has had similar contracts outside of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, under which tribal employees performed the same scale and scope of federal work as CSKT performed at the Bison Range. Under its Self-Governance agreements, CSKT employed over a dozen employees at the Bison Range. Under the 2008-2010 agreement, CSKT managed all or part of the Bison Range’s biology, maintenance, fire and visitor service programs and also staffed one of the Deputy Refuge Manager positions. Under the 2005-2006 agreement, CSKT had also employed staff in those same programs.

CSKT’s Bison Range Self-Governance agreements are exceptional in the country. No other tribe has had similar contracts outside of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, under which tribal employees performed the same scale and scope of federal work as CSKT performed at the Bison Range. Under its Self-Governance agreements, CSKT employed over a dozen employees at the Bison Range. Under the 2008-2010 agreement, CSKT managed all or part of the Bison Range’s biology, maintenance, fire and visitor service programs and also staffed one of the Deputy Refuge Manager positions. Under the 2005-2006 agreement, CSKT had also employed staff in those same programs.

The Tribes’ Natural Resources Department has extensive experience in wildlife and natural resources management, including the establishment and management of the country’s first tribally-designated wilderness area (the 91,000 acre Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness), as well as special management districts for large animals (Little Money Bighorn Sheep Special Management District, Ferry Basin Elk Special Management District) and the restoration and management of bighorn sheep populations, peregrine falcons and trumpeter swans on the Reservation.

The Tribes’ Natural Resources Department has extensive experience in wildlife and natural resources management, including the establishment and management of the country’s first tribally-designated wilderness area (the 91,000 acre Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness), as well as special management districts for large animals (Little Money Bighorn Sheep Special Management District, Ferry Basin Elk Special Management District) and the restoration and management of bighorn sheep populations, peregrine falcons and trumpeter swans on the Reservation.

The New York Times, in a September 3, 2003 editorial supporting efforts for Tribal management at the Bison Range, recognized the singular circumstances there: “The National Bison Range is an unusual case. It offers a rare convergence of public and tribal interests. If the Salish and Kootenai can reach an agreement with the Fish and Wildlife Service, something will not have been taken from the public. Something will have been added to it.”

The New York Times, in a September 3, 2003 editorial supporting efforts for Tribal management at the Bison Range, recognized the singular circumstances there: “The National Bison Range is an unusual case. It offers a rare convergence of public and tribal interests. If the Salish and Kootenai can reach an agreement with the Fish and Wildlife Service, something will not have been taken from the public. Something will have been added to it.”

The Tribal Self-Governance Act became law in 1994, authorizing tribal governments to contract operation of federal Interior Department programs of special geographic, historical, or cultural significance to them. Beginning in 1994, CSKT tried to secure a stable Tribal Self-Governance agreement with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) for partnering on Bison Range management.

CSKT and FWS signed the first Self-Governance agreement for the Bison Range in 2004. A number of staff within FWS were opposed to the Tribes’ presence, and FWS illegally terminated the agreement in December 2006. CSKT appealed that termination, resulting in the signing of a second agreement in 2008, under which the Tribes and FWS built a constructive partnership. This agreement was challenged in federal court and, in 2010, the court rescinded it on procedural grounds due to FWS having failed to properly explain its decision to apply a categorical exclusion under the National Environmental Policy Act.

After the court decision, the Tribes and FWS negotiated a third agreement and worked jointly on a draft Environmental Assessment. FWS repeatedly extended the process, and had not completed it by 2016. In 2016, FWS asked whether CSKT would support restoring the Bison Range to federal trust ownership for the Tribes. The Tribes developed draft legislation and embarked on extensive public outreach, garnering support from conservation groups, Indian tribes, and the public.

This Bison Range restoration legislation has now been incorporated into the Montana Water Rights Protection Act (S. 3019), a bipartisan bill introduced in December 2019 by Montana Senators Steve Daines (R) and Jon Tester (D).

After amendments, in December 2020 the Montana Water Rights Protection Act was incorporated into the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (HR 133), which was passed by the House and Senate on December 21, 2020 and signed into law by the President on December 27, 2020 as Public Law 116-260.