The Bison Range

In the 1870’s

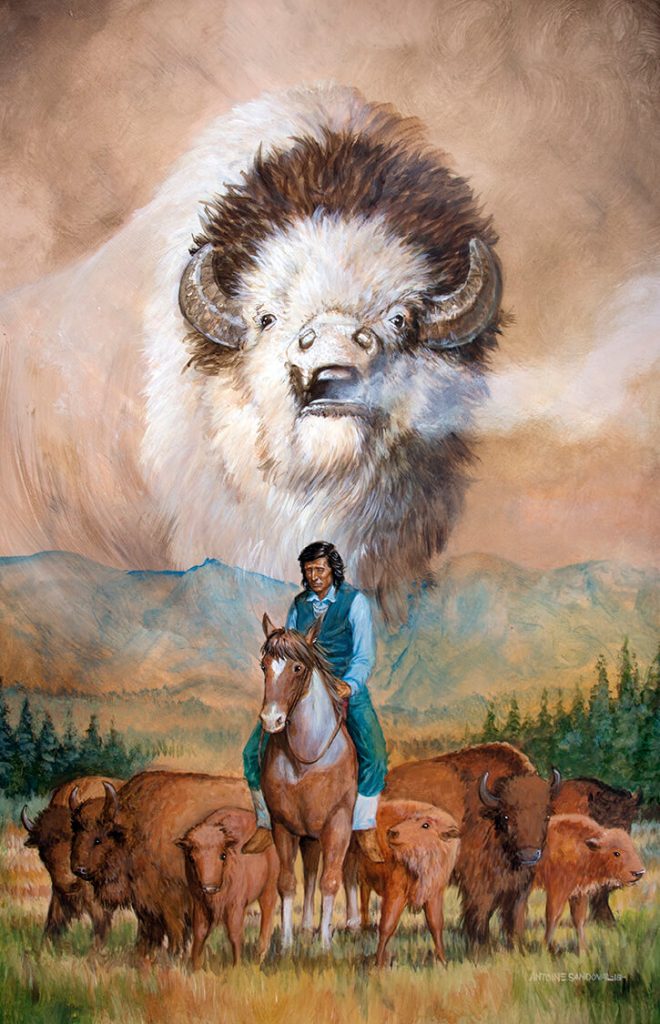

When mass slaughter put the plains bison on the brink of extinction, a Ql̓ispé (also known as Kalispel or Pend d’Oreille) man named Little Falcon Robe received approval from leaders of the Tribes to bring orphaned bison calves across the Continental Divide to the Flathead Indian Reservation for purposes of starting a herd for subsistence and conservation purposes.

Those few bison calves grew into a large free-ranging herd under the stewardship of Tribal members, who later included Michel Pablo and Charles Allard. This herd became the largest herd of plains bison in the world by the end of the 1800’s. After Charles Allard died in 1896, his estate sold his share of the Pablo-Allard herd, some of which went to the Conrad Ranch in Kalispell, Montana in the early 1900’s.

The Pablo-Allard herd ranged freely on the Reservation for decades before they were sold to off-Reservation interests in the early 1900’s due to the opening of the Reservation, over strong objection from the Tribes, for non-Indian settlement.

Eighteen bison from the Pablo-Allard herd went to Yellowstone National Park to augment its dwindling bison herd, which had consisted of an estimated 22 animals by 1902. The rest of the herd were sold to private ranches and the Canadian government.

In the Hellgate Treaty of 1855, the United States promised that the Flathead Reservation would forever be the Tribes’ permanent homeland. In exchange, the Tribes agreed to relinquish millions of acres of their aboriginal territory. The Tribes lived up to their promise but sadly, the United States did not.

In 1908-1909, despite strong objection from the Tribes, the United States unlawfully took the land from the Tribes for the Bison Range, previously called the National Bison Range. The United States paid an estimated $1.56 per acre. In 1971, the U.S. Court of Claims held that this purchase was below the fair market value of the time and therefore unconstitutional under the Fifth Amendment. They awarded the CSKT around $231,548 in compensation (approximately $14 per acre, based upon the 1912 fair market value rate). However, tribal members have for generations believed that no amount of money could compensate them for removal of the Bison Range from their permanent homeland.

After the Bison Range was established in 1908, the federal government needed to obtain animals for its initial bison population. This history is recounted in a short documentary film called “In the Spirit of Atatíc̓e: The Untold Story of the National Bison Range”, available for viewing below:

In The Spirit of Atatíc̓e

Tribal Natural Resource Management

The Tribes’ Natural Resources Department has extensive experience in wildlife and natural resources management,

including the establishment and management of the country’s first tribally-designated wilderness area (the 91,000 acre Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness), as well as special management districts for large animals (Little Money Bighorn Sheep Special Management District, Ferry Basin Elk Special Management District) and the restoration and management of bighorn sheep populations, peregrine falcons and trumpeter swans on the Reservation.

From 1994 through 2016, CSKT engaged in extensive and repeated efforts towards entering into partnership agreements with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to participate in managing the Bison Range. These contracts were authorized by the Tribal Self-Governance Act and two such agreements were in effect from 2005-2006 and 2008-2010.

The CSKT’s Bison Range Self-Governance agreements are extremely unique for the United States.

No other tribe has had similar contracts outside of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, under which tribal employees performed the same scale and scope of federal work as CSKT performed at the Bison Range. Under the Self-Governance agreements, the CSKT employed over a dozen employees at the Bison Range. During both the 2005-2006 agreement and the 2008-2010 agreement, the CSKT managed all or part of the Bison Range’s biology, maintenance, fire and visitor service programs and also staffed one of the Deputy Refuge Manager positions.

The New York Times, in a September 3, 2003 editorial supporting efforts for Tribal management at the Bison Range, recognized the singular circumstances there: “The National Bison Range is an unusual case. It offers a rare convergence of public and tribal interests. If the Salish and Kootenai can reach an agreement with the Fish and Wildlife Service, something will not have been taken from the public. Something will have been added to it.”

The Tribal Self-Governance Act became law in 1994, authorizing tribal governments to contract operation of federal Interior Department programs of special geographic, historical, or cultural significance to them.

Beginning in 1994, the CSKT tried to secure a stable Tribal Self-Governance agreement with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) for partnering on Bison Range management.

The CSKT and FWS signed the first Self-Governance agreement for the Bison Range in 2004. A number of staff within FWS were opposed to the Tribes’ presence, and FWS illegally terminated the agreement in December 2006. The CSKT appealed that termination, resulting in the signing of a second agreement in 2008, under which the Tribes and FWS built a constructive partnership. This agreement was challenged in federal court and, in 2010, the court rescinded it on procedural grounds due to FWS having failed to properly explain its decision to apply a categorical exclusion under the National Environmental Policy Act.

Bison Range Restoration

After the court decision, the Tribes and FWS negotiated a third agreement and worked jointly on a draft Environmental Assessment. FWS repeatedly extended the process, and had not completed it by 2016. In 2016, FWS asked whether the CSKT would support restoring the Bison Range to federal trust ownership for the Tribes. The Tribes developed draft legislation and embarked on extensive public outreach, garnering support from conservation groups, Indian tribes, and the public.

As a result, the Bison Range restoration legislation was incorporated into the Montana Water Rights Protection Act (S. 3019), a bipartisan bill introduced in December 2019 by Montana Senators Steve Daines (R) and Jon Tester (D).

After amendments, in December 2020 the Montana Water Rights Protection Act was incorporated into the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 (HR 133), which was passed by the House and Senate on December 21, 2020 and signed into law by the President on December 27, 2020 as Public Law 116-260. After a year of co-management, the Bison Range was fully operated by CSKT staff as of January 2022.